IMPORTANT UPDATE: Congress has changed the ACA premium subsidy amounts for 2021-2025. The marginal tax rates resulting from the phase-out of these subsidies have also changed. See this post for a graph comparing the old marginal rates with the new marginal rates. In a nutshell, the rates have gone down for incomes below 300% of the poverty level, and have gone up at higher incomes. The basic premise behind the post below still applies.

FURTHER UPDATE: As of mid-2025, the temporary changes in premium subsidy formulas from 2021 seem likely to sunset. This will cause the graphs from the original post below to be more-or-less accurate again, minus annual inflation adjustments. I may post an update with inflation adjustments in the future.

ORIGINAL POST BELOW…

In a recent thread on the MMM forums, there was a discussion about how the phase-out of ACA premium subsidies can act as a second parallel tax system to the standard federal income tax. I had always been aware of this in theory, but had previously dismissed it as a pretty minor factor for planning because the percentage of your MAGI you’ll pay for insurance after subsidies is fixed at a relatively low rate (ranging from roughly 2% of MAGI at the low end of the income scale to a bit less than 10% at the upper end of the subsidy-eligible range).

What I failed to consider was that as your income increases and the percentage of income you owe for the reference insurance plan also increases, this new percentage is applied to your entire income, not just the marginal income. This causes the marginal rate of subsidy phase-out to be greater than the percentage of MAGI now owed. In fact in many cases the marginal rate is in excess of 15%!

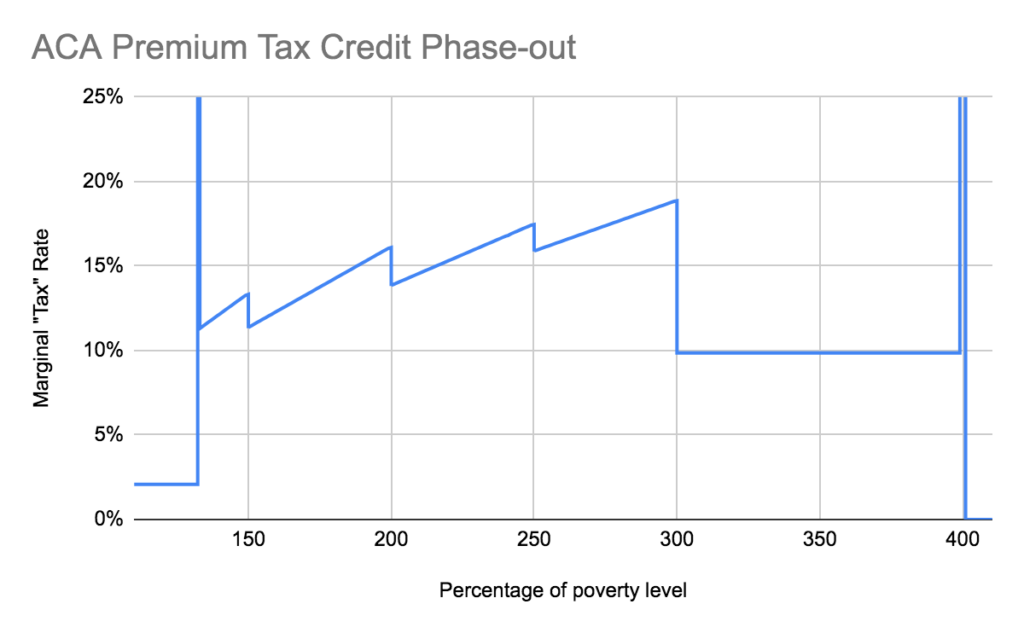

See the graph below for how this works.

Those big vertical lines represent cliffs at 133% of the poverty level (where there’s a sharp jump from 2.08% of MAGI to 3.11% of MAGI) and at 400% of the poverty level (where premium subsidies go away completely). Between the cliffs there’s a pretty big range where the marginal rate is right around 15%. Above 300% of the poverty level the applicable percentage of income is fixed at 9.86%, so that’s also the marginal rate that applies in this range.

How does this look when added on to the standard federal income tax brackets in early retirement?

Example 1: Single person

Let’s start with a pretty simple example, of a single person using the Roth conversion ladder to access their IRA funds during early retirement. All of their income is generated using this method. They claim the standard deduction and aren’t eligible for any tax credits besides the ACA premium assistance.

The blue line in this graph is exactly the same as in the first graph, representing the marginal rate for phase-out of the ACA premium tax credit for a single-person household.

The red line is federal income tax: 0% below the standard deduction, then a 10% bracket, 12% bracket, and 22% bracket. The yellow line is the sum of the two. To the right of the subsidy cliff the blue line goes to zero, so the red and yellow lines are identical at that point.

What we can see from this graph is that the total marginal rate for this individual is in excess of 20% for the entire ACA phase-out range, and in excess of 25% for a large chunk of it.

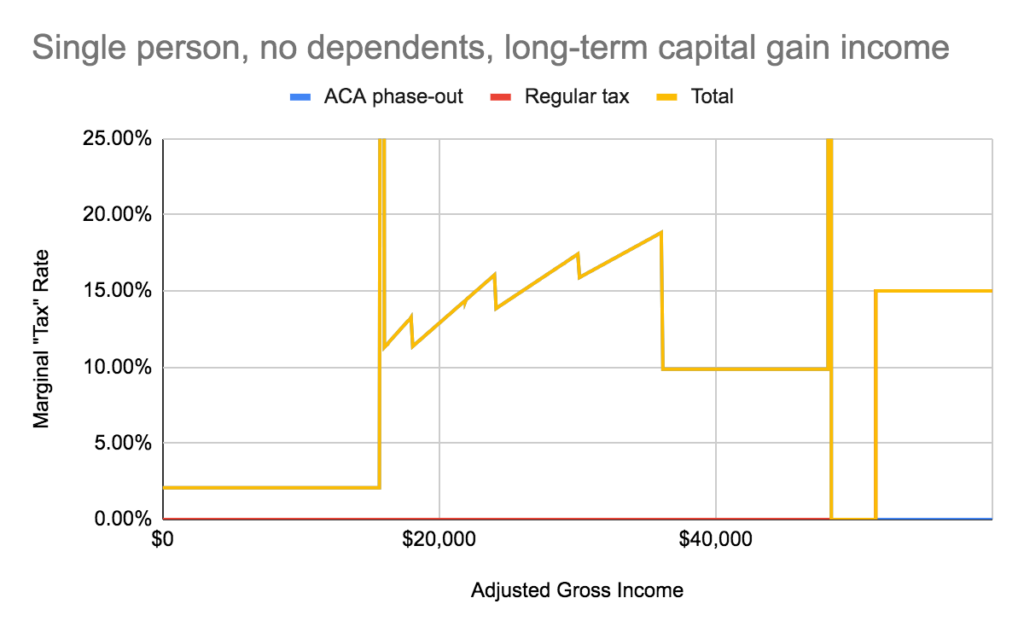

How about a single person drawing down their taxable investment account, getting all their income from dividends and long-term capital gains?

In this case the red and blue lines are hardly visible at all. During the ACA phase-out range the tax rate for long-term gains is 0%, so the yellow line overlaps the blue line. After that there’s no more ACA subsidy to phase out so the yellow line overlaps the red line.

I think this graph helps rebut the somewhat common question about whether Roth contributions make sense when taxable investments have a 0% income tax rate at lower income levels. If it’s tax-free either way, why tie the money up in a Roth IRA, right?

Well, if you’re planning to take ACA subsidies, it’s not tax-free either way. You’ll be paying for those “tax-free” capital gains in the form of lower ACA tax credits, while withdrawals of your Roth principal don’t count toward your MAGI and therefore don’t affect your ACA tax credit in the slightest.

The graph of capital gains income above is basically the same for other family sizes: only ACA phaseouts count toward the marginal rate in the phase-out range, then there’s a period of truly zero tax after the ACA cliff, then the 15% capital gains rate starts to apply later. The income levels stretch out based on family size, but the general form of the graph stays the same.

Example 2: Family of four

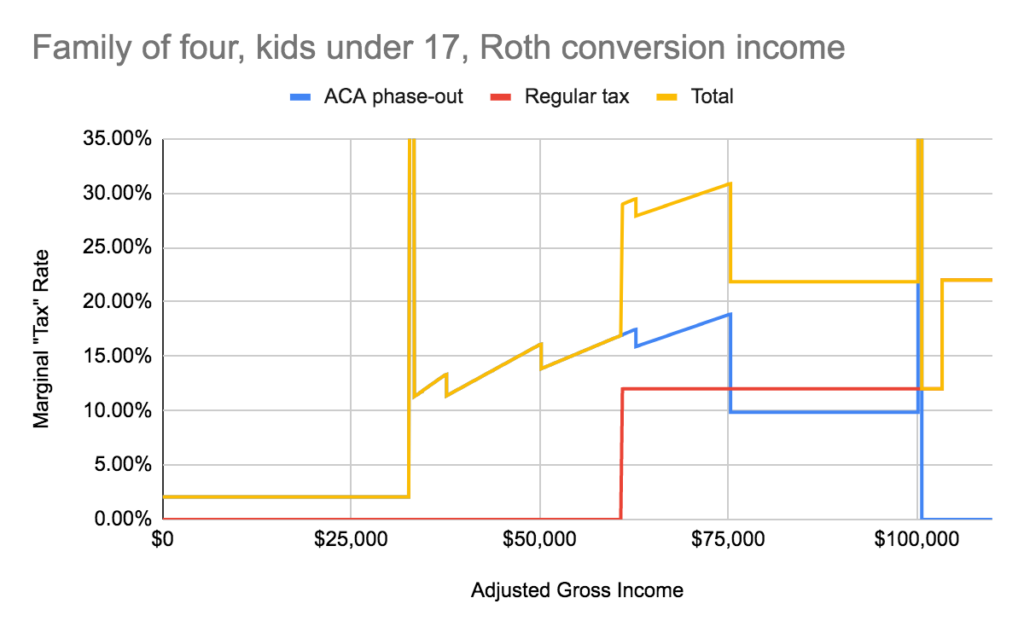

Now we’ll look at a family of four: a married couple with two kids under the age of 17. All of their income comes from Roth conversions. They claim the standard deduction, child tax credit, ACA premium tax credit, and nothing else.

This family has a pretty big range (up to nearly $61,000 in gross income) where the child tax credit erases their federal income tax liability, so only the ACA phase-out contributes to their total marginal rate. After that it looks pretty similar to the single-person example, with total rates around 30% up to 300% of the poverty level, then dropping down to 22% until the subsidy cliff.

What happens as the kids grow up? Once they hit age 17 they’re no longer eligible for the $2,000 child tax credit, but as long as they remain dependents of their parents there’s a $500 “credit for other dependents.” If both kids fall into this situation, it looks something like this:

This is starting to look a lot more like the graph for a single person. Not quite all of the ACA subsidy phase-out range has total marginal rates in the 20-30% range, but it’s pretty close.

Fast forward a few years, the kids finish school, earn their own money, and stop being tax dependents. What happens then? The parents will still be paying taxes as a married couple, and will now be using the two-person household poverty level for their ACA subsidies.

This graph has an x-axis at the same scale as the previous graphs for a four-person family. Notice that the ACA phase-out range has moved over to the left and compressed into a smaller range. This couple will need to sharply reduce their income if they want to keep paying the same amount for health insurance as before their children moved on, and maybe to keep getting any ACA subsidies at all. This is happening at the same time as they’re getting older and facing higher premium costs if they were to lose their subsidies.

Conclusions

I know that this sequence of graphs has caused me to reconsider my family’s long-term tax strategy. I had previously thought it best to focus on spending down taxable investments early on in FIRE, then focus more on Roth conversions later on.

Now that I see how the child tax credit gives us a pretty big amount of space where Roth conversions are taxed the same as capital gains, but only until the kids turn 17, perhaps accelerating some of those Roth conversions would make sense in order to build up some more basis in those accounts and allow us to more easily reduce our income when we have no more dependents to declare.

I’m also starting to think the standard advice in the FIRE community to prioritize pre-tax retirement accounts over Roth while in the accumulation phase may be misguided. The assumption is that someone who spends a fraction of their income while working will be very likely to retire into a lower tax rate. As we can see in these graphs that isn’t such a sure thing when you also consider the ACA subsidy phaseout as part of your marginal tax rate in retirement.

Someone earning enough to hit the 35% bracket during their career would still be seeing a pretty definite win by deferring a bunch of taxable income until retirement. For people even in the 24% bracket while working, we can see plenty of relatively low retirement incomes where you’ll be paying more than that.

Of course if you would rather buy insurance from a private carrier instead of relying on Medicaid you’ll need to come up with some level of income that counts toward MAGI in retirement. But maybe the best thing for most folks with relatively normal salaries to do is to save just enough pre-tax to hit the very low end of the ACA subsidy range each year in retirement and go with Roth for the rest.

What do you think? I’d love to hash this out more in the comments.

Just wanted to say thanks for all the work. It gave me a bit more insight into the ACA/RCL debate.

I’m interested to hear your thoughts on this for someone 15 or so years from early retirement. I am expecting there to be political change before I retire, possibly medicare for all or some form of single-payer system. How would you weigh this factor into deciding if Roth contributions are worth it?

Political change of some sort is inevitable. What will that look like exactly? Impossible to say for sure.

The main thing that determines whether you should make traditional or Roth contributions is your overall marginal rate now compared to later. While it’s pretty easy to find out what your current marginal rate is, there are a lot of guesses that go into predicting your rate in the future. How much will you spend? What types of accounts will that spending come from? How will the markets perform? Will the tax brackets for your expected level of income change, and in what direction? Will we further nationalize the health care system?

In the end you just have to make the best guesses you can and act accordingly. There’s something to be said for a bit of diversification between different tax shelters so that you’re in a reasonable position to adapt to whatever changes may occur.

Just one follow-up question to this:

I for sure agree that politics is up in the air and could go any which way.

Follow up –>Wouldn’t the applicable tax rate be the future effective rate, rather than the future marginal rate? For instance, right now my wife and I can avoid the 22% bracket with 401k contributions, so I agree that the marginal rate is the current applicable rate. However, in Early Retirement, the majority of our taxable income will come from 401K-> Roth IRA rollovers, so the applicable rate should be the effective tax rate for those rollovers, not the marginal rate at that time, since the effective rate represents the total tax rate on those dollars that would have been taxed at 22% initially. With that in mind, even if our income was projected to be the exact same as our spending needs in retirement, a traditional account would still be preferable to a Roth, since the effective tax rate of ~$100K AGI is still down near 10% thanks to the Standard deduction and lower tax tiers. For that reason, I find it hard to believe that a Roth 401k could ever be superior to a traditional 401k, unless your earnings for the year are in the 0% or possibly 10% marginal bracket.

The correct comparison really is marginal rate now vs. marginal rate later. Using the effective tax rate for the future value is a common misconception, but is incorrect nonetheless.

Here’s why:

You already have some amount invested, and you can expect that existing investment to create a certain amount of taxable income in retirement. At some point you’ll have enough in there that you’ll expect to be able to fill up the standard deduction in retirement even without any more contributions.

Why count this standard deduction toward your effective rate when deciding what to do with new money? That 0% bracket is already full for the rest of your life. Any money you put in this year will be withdrawn on top of money that you’ve contributed in previous years. That’s why we need to look at marginal rates.

Let’s say for the sake of argument that you currently have $250k invested in a pre-tax retirement account and you estimate your existing savings will triple in value by the time you retire in 15 years. That will leave you with $750k. If you use the 4% rule, you’ll be taking out $30k annually just from money you’ve already contributed.

That’s enough to eat up the standard deduction and get you into the 10% bracket as a married couple. By my math, you’d be paying a hair under 2% effective rate on this $30k of income.

Now this year, suppose you have another $25k available to save. Do you go with traditional or Roth? Again, we expect this money to triple by the time you retire. If you go with traditional that means an extra $75k in your stash when you retire, throwing off $3k of taxable income each year.

Your effective tax rate would only go up a fraction of a percent, but you’d be paying 10% of regular federal income tax on the withdrawals attributable to this year’s contribution. ACA subsidy phase-outs would tack on another ~15%. That’s why we need to look at marginal rates.

As long as the ACA (or something like it that uses an income-based formula) exists, you can see from this post that it doesn’t take a very high income to exceed your current 22% marginal rate with taxes and ACA phase-outs combined.

How long will we have the ACA in something similar to its current form? Your crystal ball is as good as mine. If you had asked me shortly after the 2016 election to make a guess about that I would have said the whole thing would be repealed in a year or two tops. Didn’t happen. Change moves slowly in Washington.

Thank you, Seattlecyclone. I don’t know why I didn’t think of it that way before, but that makes a lot of sense.

Essentially, it boils down to saving enough pre-tax to fill up the standard deduction every year and then reevaluating once the annual distribution would begin to fill up each new income tax bracket. Definitely something for me to think on, especially considering the timing of having children and the ability to offset more income with the child tax credit for a certain period of time. I may consider trying to reallocate a portion of my 401k contributions to Roth in attempt to fill up the 12% bracket and squeeze fill up the 12% bracket but not hit the 22% yet. Thanks again for the insight!

Sorry if this was explained in your “family of four” example, but does claiming the child tax credit require a minimum amount of earned income?

I haven’t looked at the forms in depth, but a couple of web searches and a cursory glance at some worksheets convinced me that you’re only eligible for the child tax credit if you have at least $2,500 in earned income during the year. A low bar, sure, but if you’re truly retired and have no earned income, I’m curious if you miss out on this tax break.

Note: I think I was mistaken (I mixed up the “Line 14 worksheet”–which uses earned income–with the “Child Tax Credit and Credit for Other Dependents Worksheet”–which uses adjusted gross income).

Tax Caster confirms your results (i.e. the non-refundable child tax credit doesn’t require earned income). I entered MFJ, 1 child, $40,000 in short-term gains (and no other income), and Tax Caster showed a $2k credit.

Having said that, there was no shortage of sites (e.g. smartasset.com) that indicate that earned income is needed to qualify for the child tax credit, but they’re probably just conflating the non-refundable and refundable parts of the credit.

Feel free to delete my comments 🙂

It gets even more interesting and harder to analyze if you have kids in college. As I’ve mentioned over on MMM, the FAFSA EFC effectively acts as a fourth parallel tax system (in addition to federal, state, and ACA PTC effects).

For 2017, I targeted an AGI of under $25K in order to qualify for the automatic zero EFC, but I left several nonrefundable tax credits on the table.

For 2018, I targeted an AGI that would sop up all of my nonrefundable credits and leave me with a tax bill of about $3 or $4. I lost the automatic zero EFC, but the financial aid was still very good.

For 2019, I targeted just under $50K AGI, to maximize my Roth conversion amounts and still qualify for FAFSA SNT (simplified needs test, where the formula excludes parental and student assets and is just based on income).

For 2020, I am back to my 2018 approach: Roth convert enough to sop up all the refundable credits, but don’t do more. The reason for this is that my marginal rate above that point is about 53%, which is higher than I project I will be paying at age 75. The reason for this is federal plus state plus ACA subsidy loss plus FAFSA EFC increase for two kids in college.

Once the FAFSA effect drops off, that will cut off about 18% of marginal rate and I’ll re-evaluate. I tentatively plan to convert up to just under 400% of FPL.

Question: Do you have any suggestions for being able to create graphs like yours for my own particular situation other than the case study worksheet? (I’d like to generate my own but don’t own Excel.)

I made these graphs in Google Sheets. You’ll need to create a table of income compared to tax (or insurance premiums, or tuition) at that income. Then you’ll need to calculate the marginal rate at each row. This will be the difference in tax between this row and the previous row, divided by the difference in income between the two rows. Once you have this, just add a chart with the income on the x-axis and the marginal rate on the y-axis.